The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines Environmental Justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Further, the EPA states that “fair treatment,” used in this context, means that “no group of people should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, governmental, and commercial operations or policies.”

Other definitions exist, but they generally share the EPA definition’s two themes: 1) distributive justice – the equitable distribution of environmental risks and benefits, and 2) procedural justice – the fair and meaningful participation in decision-making.

While the idea of environmental justice has long existed, the movement in the U.S. was sparked by the Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) Protests in Warren County, North Carolina, in 1982. There, low-income, rural, and overwhelmingly Black residents protested the state’s decision to construct a landfill in their county for the purpose of dumping 6,000 truckloads of soil laced with PCBs. And although the residents were unsuccessful in stopping the landfill, the six weeks of protests brought national attention to the disproportionate impacts of environmental pollution on minority communities.

Source: NCEL Celebrates Black History Month | National Caucus of Environmental Legislators (ncelenviro.org)

Still, progress has been slow.

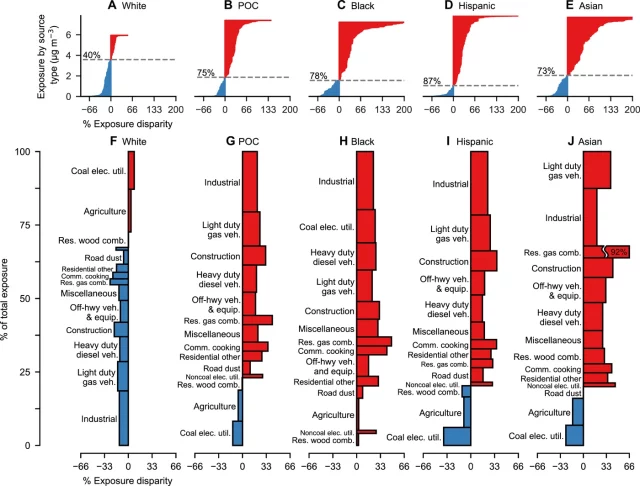

Research published in April 2021 in Science Advances, which focused on PM2.5 – the ambient fine particulate matter air pollution responsible for 85,000 to 200,000 deaths per year in the U.S. – found that “most emission source types – representing ~75% of exposure to PM2.5 in the U.S. – disproportionately affect racial-ethnic minorities.” This comes after research published in August 2012 in Environmental Health Perspectives found that overall levels of particulate matter exposure for people of color were higher than those for white people.

Source: PM2.5 polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States | Science Advances

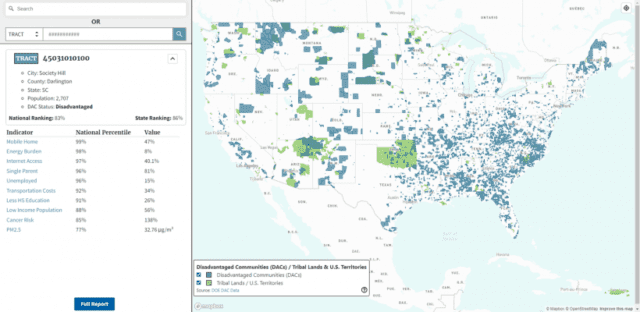

President Biden seems to recognize these disparities. On his first day in office, he issued Executive Order 13990, directing the federal government to advance environmental justice where agencies “failed to meet that commitment in the past” and “to hold polluters accountable, including those who disproportionately harm communities of color and low-income communities.” One week later, Executive Order 14008 established the Justice40 Initiative, with a goal that at least 40 percent of the overall benefits from certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities (DACs).

Shortly thereafter, the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Economic Impact and Diversity, in order to guide the DOE’s implementation of Justice40, identified eight policy priorities, one of which aims to decrease environmental exposure and burdens for DACs. Because DACs are more likely to be located near heavily traveled highways, oil refineries and petrochemical plants, a shift from gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles would reduce toxic emissions from these sources, thus lowering the negative environmental impacts on these communities.

Source: Justice40 Initiative | Department of Energy

In 2021, there were an estimated 6,619,000 fleet cars and trucks under 19,501 GVW. While that represents a small fraction of total vehicles in the U.S., fleets are uniquely positioned to dramatically alter the electric vehicle (EV) landscape.

Corporate sustainability mandates and promising cost-of-ownership numbers suggest the transition to electrified fleets could occur more quickly and dramatically than among passenger vehicles. As this transition occurs, more charging stations will be added to meet demand, giving DACs increased access and reducing “charging deserts.” This will help address another Justice40 policy priority – to “increase parity in clean energy technology (e.g., solar, storage) access and adoption in DACs.”

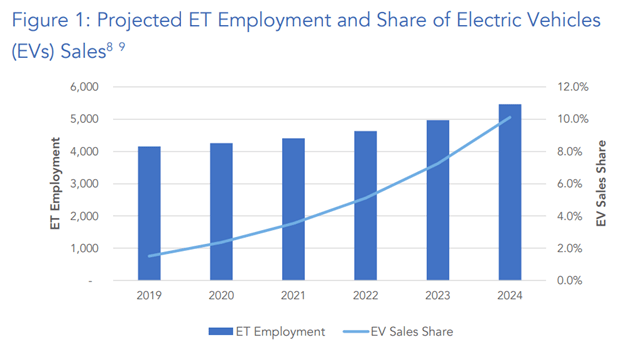

As transportation trends towards electric, opportunities to put the “justice” in environmental justice are plentiful and extend beyond the scope of Justice40. For example, an April 2021 report from Advanced Energy Economy, which examined the economic and workforce potential of New York’s expanding electric transportation industry, revealed that electric transportation growth offers opportunities across the value chain and that “workers in adjacent and support industries are generally representative of the overall New York state workforce.”

Source: Microsoft Word – AEE NY ET Supply Chain Report.docx (advancedenergyunited.org)

So, while the Biden administration has done a commendable job supporting EVs and environmental justice – and the link between the two – the responsibility isn’t theirs alone. Utilities, local governments, and yes, private businesses, are also on the hook for creating an environment that works for everyone.

Sage McLaughlin

Director of Business Development